- Home

- Peter Maas

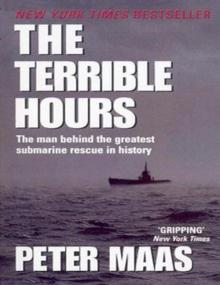

The Terrible Hours

The Terrible Hours Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Praise for Peter Maas

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Epilogue

Afterword

Copyright

About the Book

On the eve of World War II, the Squalus, America's newest submarine, plunged to the bottom of the North Atlantic. Miraculously, thirty-three crew members still survived in the stricken vessel. While their loved ones waited in unbearable tension onshore, their ultimate fate would depend upon one man, US Navy officer Charles ‘Swede’ Momsen – an extraordinary combination of visionary, scientist and man of action. In this thrilling true story, prize-winning author Peter Maas vividly re-creates a moment-by-moment account of the disaster and the man at its centre. Could he actually pluck those men from a watery grave? Or had all his pioneering work been in vain?

PRAISE FOR PETER MAAS

“Mr. Maas proves once again there is little he

cannot achieve with the written word.”

—New York Times Book Review

“Peter Maas has established himself as one

of the nation’s most respected nonfiction authors.”

—Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Peter Maas offers insights only the

best reporters can unearth.”

—Boston Globe

“Each time I pick up Maas, I feel that I have been

given a backstage pass to an American moment.”

—Los Angeles Times Book Review

The Terrible Hours

The Man Behind the Greatest Submarine Rescue in History

Peter Maas

In memory of an extraordinary man, Swede Momsen,

whose likeness rarely passes our way.

“The world, so to speak, began with the sea, and who knows but that it will also end in the sea!”

CAPTAIN NEMO, in Jules Verne’s

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea

1

IT WAS A Tuesday, May 23, 1939.

In New York City, Bloomingdale’s department store was promoting a new electronic wonder for American homes called television.

With great fanfare, United Airlines began advertising a nonstop flight from New York to Chicago that would take only four hours and thirty-five minutes.

In baseball, a young center fielder for the New York Yankees named Joe DiMaggio was headed for his first major league batting title.

The film adaptation of the novel Wuthering Heights, starring the English actor Laurence Olivier in his first hit movie, was in its sixth smash week.

Another novel destined to become an American classic, Nathanael West’s portrait of Hollywood, The Day of the Locust, was dismissed in the New York Times as “cheap” and “vulgar.”

In Canada, the visiting British monarchs, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, met the Dionne quintuplets for the first time.

In London, Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy advised an association of English tailors that they would never gain a foothold in the American market unless they stopped making trouser waistlines too high and shirttails too long.

In Berlin, as Europe teetered on the brink of war, Hitler and Mussolini formally signed a military alliance between Germany and Italy with a vow to “remake” the continent. In Asia, meanwhile, Japan had finished another week of wholesale carnage in China.

THAT TUESDAY MORNING, in the picture-postcard sea-coast town of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, with Federal architecture and cobblestone streets dating back to the late eighteenth century, Rear Admiral Cyrus W. Cole, commandant of the Portsmouth Navy Yard, the nation’s oldest, received a group of visiting dignitaries. Cole was a peppery little man with an imposing head and a piercing gaze that made him seem larger than he actually was. Although not a submariner himself, he had a particular affinity for the men who manned the Navy’s “pigboats.” His only son served on one, and before coming to the Portsmouth yard, which specialized in submarine construction, Cole had commanded the Navy’s underseas fleet. Now he liked to wisecrack, “They sent me back to see how they’re built.”

When one of his visitors asked the admiral if he thought the United States might be drawn into the looming conflict in Europe, he said he hoped not. If it proved otherwise, though, any enemy would rue the day.

You hear a lot about those German U-boats, he declared, but they couldn’t compare with the submarines that the Portsmouth yard was sending down the ways. This very afternoon the newest addition to the fleet, the Squalus, would return to her berth after a series of test dives. He promised a tour, so they could see her for themselves.

“Squalus? What kind of name is that?”

Cole confessed that he’d had to look it up. “It’s a species of shark. A small one. But with a big bite,” he added, smiling.

Then Cole passed his visitors over to Captain Halford Greenlee, the yard’s industrial manager. Their arrival, arranged at the last minute, had forced Greenlee to cancel plans to go down to the overnight anchorage of the Squalus and board her that morning. Greenlee had been especially looking forward to it. His son-in-law, Ensign Joseph Patterson, was the sub’s youngest officer.

“Sorry you couldn’t go out with her today,” Cole said.

“It’s not the end of the world,” Greenlee replied. “I can always catch her another time.”

TWO REPORTERS FOR the Portsmouth Herald at the yard on assignment for other matters were the first outsiders to hear the news. After frantically gathering whatever scraps of information were available, they raced back to the paper.

Minutes later, just past two P.M., the first stark, bell-ringing bulletin clattered over Associated Press teletypes to newspapers and radio stations throughout the country:

SUBMARINE SQUALUS DOWN

OFF NEW ENGLAND COAST

2

THE PORTSMOUTH NAVY Yard occupied an island three miles upstream from the mouth of the Piscataqua River, a twisting, tidal millrace that separated New Hampshire and Maine. To avoid contending with the Piscataqua’s seven-foot highs and lows during which an ebb current could reach a full twelve knots, the Squalus, after a day of training exercises, had remained overnight in a rockbound cove near where the river emptied into the North Atlantic.

The wife of her skipper, Lieutenant Oliver Naquin, had decided to give their two young children a special treat. In the late afternoon, she had driven down from Portsmouth to the cove where the Squalus stretched low in the water behind an ocean breakwater. But Naquin had the crew busily engaged in internal housekeeping preparatory to an anticipated inspection when the sub returned to the yard, and when they arrived, nobody was in sight to answer their shouts and waves. Frances Naquin often thought of this during the terrible hours that lay ahead.

THE SQUALUS WAS the Navy’s newest fleet-type submarine, 310 feet long, twenty-seven feet wide, displacing 1,450 tons. Her rated surface speed was sixteen knots. On battery power, while submerged, she could do nine knots. Seemingly, every care and precaution had been lavished on her. She was state-of-the-art—and deadly. Topside along her length she had a slotted teakwood deck. Above the deck rose an oval steel island some twenty feet high with a big “192” painted in white on each side. It was officially called the brid

ge fairwater, more popularly known as the conning tower.

It also had two hydraulically operated valves that functioned on the same principle as ordinary faucets. Named the high inductions, one was an opening thirty-one inches across that fed air to her four 1,600-horsepower diesel engines when she cruised on the surface. The other, sixteen inches in diameter, ventilated the boat. Mounted on the deck as well was a three-inch gun to finish off crippled targets or for use as a last resort to fight off an attacking enemy ship.

America in a very real sense rode with the Squalus that Tuesday in May. Her crew represented twenty-eight states. Almost half were married. Most were experienced petty officers, and ninety percent of them wore the silver twin-dolphin insignia designating them as qualified submariners. Of her normal complement of fifty-seven officers and men, only one was missing, a machinist’s mate hospitalized after suffering a bad concussion when he was conked on the head by an errant softball during a game the previous Saturday against the crew of a sister submarine, the Sculpin.

Like the majority of the enlisted men, Gerry McLees had joined the Navy in the early years of the Great Depression. For McLees, growing up then had the added misery of the unparalleled drought in the prairie states where the topsoil literally dried up and blew away. His father’s once-productive 360-acre Kansas farm was barely able to sustain the family of six. So, at age eighteen, he hitchhiked to a recruiting office in Topeka with fifty cents in his pocket. He never regretted it. On leave after boot camp in San Diego, he always remembered the last leg of his train ride home during which he had to keep a wet handkerchief pressed to his face to repel the relentless wind-swept dust.

All submariners were volunteers. Part of the attraction, of course, was money. Beginning with a base pay of fifty-four dollars a month for an ordinary seaman, a submariner in those days got a twenty-five percent bonus along with a dollar a dive “not to exceed fifteen dollars a month.” But beyond that, there was also far less protocol, which was so prevalent in the surface fleet, more intimacy and camaraderie, a sense of belonging, of being part of something special.

To an outsider, with the incredible array of paraphernalia packed inside her hull, the Squalus might seem a claustrophobic nightmare. But for McLees, now an electrician’s mate third class, she was unbelievably spacious compared to the subs he had first served on. And best of all, she not only was air-conditioned, but boasted toilets.

McLees hung out off duty with two other bachelor sailors, Lloyd Maness, a lanky North Carolinian, also an electrician’s mate, and a muscular torpedoman of Portuguese descent, Lenny de Medeiros, from New Bedford, Massachusetts. After Saturday’s softball game, they repaired to a beer joint they favored, the Club Cafe, where they could run tabs till payday. Maness was the object of some ribbing. In a week, he was to be best man at the wedding of another crewman.

“You learn your lines yet?” McLees asked.

“Lines, what lines?”

“When they ask for the ring, ain’t you supposed to say something?”

“Nobody said nuthin’ about that.”

“Well,” said de Medeiros, “what about the ring? You got it in a safe place?”

“She’s holding it,” Maness replied sheepishly.

AT SEVEN-THIRTY A.M., the Squalus edged seaward from her anchorage in the cove.

Her keel had been laid at Portsmouth in October 1937. The following September she was launched before a cheering crowd as the Frank E. Booma Post American Legion band from Portsmouth played “Anchors Aweigh” and the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Next came the months of installing her diesel engines, electric motors and the rest of the apparatus that would give her life. Many members of her crew started reporting for duty long before the work was completed, and as they watched her take shape, they became acquainted with every facet of her delicate innards. The tricky business of running her demanded nothing less. A single mishap in any of the scores of steps involved in her operational routine could transform her instantly from a sleek underseas prowler into a tomb for them all.

In three weeks she was scheduled to undergo formal trials before joining the fleet. Today she would make her nineteenth test dive in the ocean. Her first submergence, to ensure that she was watertight, had taken place in early April while she was still in her berth. Afterward, the big thirty-one-inch induction valve failed to open properly. The entire valve assembly was taken apart, put back together, and had not caused further trouble. The first tentative dip beneath the surface—her deck and superstructure not yet finished—occurred later in the month in Portsmouth Harbor. After she surfaced, one of her motor bearings developed trouble. It was a relatively minor malfunction. Then, during one of her ocean dives, the electrical wiring connecting a torpedo tube to its recorder had briefly failed.

The practice dive this morning was especially important in order to pass final muster. In combat, it could mean the difference between life and death. Riding with her ballast tanks high and dry, allowing her to proceed at top speed on the surface, the Squalus had to complete an emergency battle descent that would drop her to periscope depth—fifty feet—in sixty seconds. In an earlier run-through, she had missed her target time by five seconds. Oliver Naquin was determined to do a lot better in this second run-through.

Naquin stood on the bridge as the Squalus headed in a southerly direction. He was quite pleased with the way things had been progressing. The crew seemed to be meshing together nicely, and he had been especially impressed by the way his boat handled at slow speeds under water during dummy torpedo firings.

To his left, he passed a string of rocky desolate islands—the Isles of Shoals—lying parallel to the coast. They had a special history. English fishing companies had set up shop there in 1615, five years before the Mayflower’s Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. And on one of them, Smutty Nose Island, rumors of buried pirate treasure proved to be true when a trove of silver and gold was unearthed.

The thirty-five-year-old, hawk-nosed Naquin, a 1925 graduate of Annapolis, had been born and raised in Louisiana. In his youth, he’d been a talented trumpet player, good enough to have been offered a tryout with Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra, one of the big dance bands of the era. But life on the road wasn’t for him, and he did a one-hundred-and-eighty-degree turn into the Navy.

For an officer like Naquin, submarine service offered a quick career path to his own command. And now, everything had gone just the way he’d hoped.

On the bridge with him was chain-smoking Harold Preble, enjoying a last Camel before the dive. Preble, the civilian test superintendent at the yard, was on board to ensure that the Squalus performed up to par mechanically during her training runs. For nearly twenty-two years he had been doing this for every submarine that was Portsmouth-built. And although it wasn’t his province, he privately noted how well the crew carried out its tasks. He credited much of this to Naquin, who rarely, if ever, raised his voice. Naquin’s frosty blue eyes appeared to be more than sufficient to keep every man on his toes.

All in all, Preble considered the Squalus the finest submarine he’d ever been on. He even rated her better than the Sculpin, the sister sub she had followed down the Portsmouth ways. He couldn’t recall fewer problems in a new boat. So far, there had been nothing more than a stuck valve, a hot bearing, and a loose electrical connection. Except for faster reloading of her torpedo tubes, he felt that Squalus was ready to pass her sea trials.

Overhead, Naquin watched the morning sun begin to fade behind a bank of ominous gray clouds scudding across the sky. With the warm waters of the Gulf Stream and the frigid Labrador Current both lurking in the neighborhood and causing sudden dense fogs, the only true predictability about the weather was its unpredictability. The wind intensified and began kicking up a nasty chop, shooting sheets of white over the bow. Off to his right, two lobstermen were already heading back to port.

“It looks like a good day not to be on the surface,” Naquin remarked to Preble.

THE SPOT NAQUIN had chosen for the d

ive was about five miles southeast of the Isles of Shoals.

Beneath his feet, inside the double-hulled sub and her ballast and fuel tanks, the Squalus was divided into compartments that could be sealed off from one another by oval watertight doors.

In the bow was the forward torpedo room with its four torpedo tubes. Twenty-one-foot-long torpedoes were ranged in racks on each side with a system of pulleys to swing them into position for loading. Bunks for some of the crew were interspersed among them.

Next came the forward battery. Naquin’s minuscule stateroom was there, as well as quarters for the four other commissioned officers and four chief petty officers. It also had a pantry and dining area. A hatch in the passageway led down to half of the 126 lead-acid storage cells on board, each weighing 1,650 pounds, that powered the Squalus beneath the surface.

Directly under the conning tower was the nerve center of the sub, the control room, where her two periscopes came to rest. All the elements that made her tick were located here—her internal communications center, the wheels that moved her diving planes up or down, the levers that flooded her ballast tanks and emptied them again. Here, too, was the control board that showed whether she was secure against the sea before she plunged into it.

Through a watertight door, the rest of her underwater power was in the after battery compartment on the other side of the control room. Here was where most of the crew slept and all of it ate. First were thirty bunks in stacks of three. Then came the galley and mess tables. Below was the second half of the sub’s storage cells.

Like Gerry McLees, another electrician’s mate, John Batick, found the Squalus a revelation. She was roomier, faster and more maneuverable than any sub he’d ever served on. With his denim sleeves rolled high to exhibit a tattooed representation of his wife, Batick never ceased to be amazed that he could drink a cup of coffee in the crew’s mess without jamming his elbow in somebody’s teeth.

The Terrible Hours

The Terrible Hours